Posted on November 2, 2013 by ejfadmin

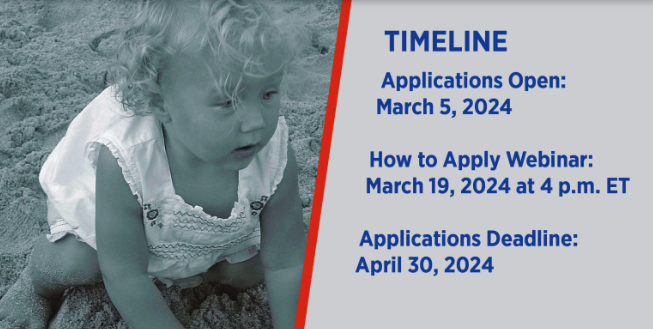

When my two-year-old daughter, Emily, passed away from a tragic medication error in 2006, my primary concern as her father was to make sure that her story and the significant “lessons learned” be brought forward and that the internal systems in medicine be subsequently modified so that others wouldn’t suffer a similar fate, over and over again. Shortly after her death, I decided to become a full-time patient safety advocate, focusing the core of my work on being an active part of the solution to preventable medical errors. When I first began to educate myself on preventable medical errors in our nation, I was astonished to find that many sources were estimating that over 200,000 people die every year in the United States from preventable medical errors. In a more recent article from the Journal of Patient Safety (September 2013 – Volume 9 – Issue 3 – p 122–128) titled “A New, Evidence-based Estimate of Patient Harms Associated with Hospital Care”, I was completely horrified to find that now, in 2013, the revised estimated number of deaths from preventable medical errors in the United States is actually over 400,000 a year! This makes preventable medical errors in our nation the third leading cause of death, only after heart disease and cancer.

As Emily’s father, and more importantly, someone who has devoted the remainder of their life to being a patient safety and caregiver advocate focused on being a part of the solution, I’ve always taken issue with the simple word “preventable”. To me, the word “preventable” implies that we can, in fact, stop or impede something from happening only if we can acknowledge and anticipate that an event will occur and, consequently, implement the appropriate measures needed to “prevent” something from happening. However, with that notion in mind, in order to prevent something from happening (i.e., preventable medication errors, etc.), you absolutely must be PROACTIVE in terms of your approach to exactly what you’re trying to prevent. This is where The Emily Jerry Foundation’s key technology partner in patient safety, Codonics, and their Safe Label System (SLS) come into play at the upcoming American Society of Health System Pharmacists Midyear Meeting, in Orlando Florida, next week.

Beginning on Monday, December 8th, through Wednesday the 11th, I will be giving five minute presentations in the Codonics booth #1551 each day at 11:45, 12:30 and 1:30. There really is no better time for our nation’s great hospitals to step up and increase patient safety through technologies that can help prevent medication errors. Let’s not wait for another tragic event like Emily’s to occur. If you are attending the ASHP Midyear Meeting, I encourage you to join me to learn about technology available to help you prevent medication errors. Together, we can ensure that systems are put into place and eliminate medication errors…forever.

Beginning on Monday, December 8th, through Wednesday the 11th, I will be giving five minute presentations in the Codonics booth #1551 each day at 11:45, 12:30 and 1:30. There really is no better time for our nation’s great hospitals to step up and increase patient safety through technologies that can help prevent medication errors. Let’s not wait for another tragic event like Emily’s to occur. If you are attending the ASHP Midyear Meeting, I encourage you to join me to learn about technology available to help you prevent medication errors. Together, we can ensure that systems are put into place and eliminate medication errors…forever.

I’m absolutely certain that many people will ask the question, “How would Codonics Safe Label System (SLS) have saved your daughter, Emily?”. My answer is this: If the facility had been proactive about modifying their systems through the implementation of clinically proven technology, similar to Codonics (i.e., bar code scanning of vials with subsequent printing of labels with accurate information of concentrations, etc.) to reduce the probability of “human error” entering into the equation during the course of treatment, I am convinced Emily would still be with us today. Bottom line, prior to my daughter’s tragic death, due primarily to the initial cost associated with the implementation of proven technology available at that time it’s my opinion that the facility was in denial that a tragic medication error like Emily’s could even actually occur at their facility. After all, they were, and still are, a leading pediatric facility in the United States. Many of the top facilities in our nation still have this underlying attitude that a horrible medication error like Emily’s could “never” happen at their facility. Bottom line, these types of errors WILL in fact occur, and statistically they will happen, it’s just a matter of when! With that being said, our nation’s world-renowned medical facilities can choose to either modify their internal systems in a proactive way, before a tragic medication error occurs, or wait to react after there has been a loss of life and a tragic event actually happens. Along those lines, I also believe that as we move forward with healthcare reform and facilities all have to do so much more with less and less financial resources, I still think that our medical facilities in the United States will make the right choices with those limited funds. After learning Emily’s story, I believe they will choose to be proactive, making the necessary expenditures in terms of modifying their internal systems with the “smart implementation” of technology like Codonics SLS in their medical facilities. I look forward to seeing you in Orlando.

I’m absolutely certain that many people will ask the question, “How would Codonics Safe Label System (SLS) have saved your daughter, Emily?”. My answer is this: If the facility had been proactive about modifying their systems through the implementation of clinically proven technology, similar to Codonics (i.e., bar code scanning of vials with subsequent printing of labels with accurate information of concentrations, etc.) to reduce the probability of “human error” entering into the equation during the course of treatment, I am convinced Emily would still be with us today. Bottom line, prior to my daughter’s tragic death, due primarily to the initial cost associated with the implementation of proven technology available at that time it’s my opinion that the facility was in denial that a tragic medication error like Emily’s could even actually occur at their facility. After all, they were, and still are, a leading pediatric facility in the United States. Many of the top facilities in our nation still have this underlying attitude that a horrible medication error like Emily’s could “never” happen at their facility. Bottom line, these types of errors WILL in fact occur, and statistically they will happen, it’s just a matter of when! With that being said, our nation’s world-renowned medical facilities can choose to either modify their internal systems in a proactive way, before a tragic medication error occurs, or wait to react after there has been a loss of life and a tragic event actually happens. Along those lines, I also believe that as we move forward with healthcare reform and facilities all have to do so much more with less and less financial resources, I still think that our medical facilities in the United States will make the right choices with those limited funds. After learning Emily’s story, I believe they will choose to be proactive, making the necessary expenditures in terms of modifying their internal systems with the “smart implementation” of technology like Codonics SLS in their medical facilities. I look forward to seeing you in Orlando.

Posted on November 1, 2013 by ejfadmin

by Christopher Jerry and Michael Wong

In his recent article, “A SEC for Health Care?”, Dr. Peter Pronovost, PhD, FCCM (Professor, Departments of Anesthesiology/Critical Care Medicine and Surgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Medical Director, Johns Hopkins Medicine Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality) discusses the tremendous variability in the quality and measures of healthcare provided across this country:

Depending where you look, you often get a different story about the quality of care at a given institution. For example, none of the 17 hospitals listed in U.S. News and World Report’s “Best Hospitals Honor Roll” were identified by the Joint Commission as top performers in its 2010 list of institutions that received a composite score of at least 95 percent on key process measures.

As an illustration of the variability of quality, the Emily Jerry Foundation recently released its “2013 National Pharmacy Technician Regulation Scorecard”. The development of this scorecard was prompted by the heartbreaking story of what happened to two year old Emily Jerry.

Emily had waged a successful battle against cancer. Her treatment had been so successful that her last MRI clearly showed that the tumor miraculously disappeared. In fact, three radiologists had to review her MRI films due to the fact that there wasn’t even any residual scar tissue left. Emily’s doctors said it was as if she never had cancer! Regardless she was scheduled to begin her last chemotherapy session on her second birthday, February 24, 2006. This last treatment was just to be sure that there were no traces of cancer left inside of her little body. Tragically, it was not cancer or the reoccurrence of cancer that ended Emily’s life. She was killed by an overdose of sodium chloride in the last chemotherapy IV bag she received.

Shortly after Emily’s tragic death, it was determined that a pharmacy technician, who did not have the proper training or core competency to be compounding IV chemotherapy, had made the deadly compounding error. The primary reason the pharmacy technician involved in Emily’s death lacked the core competency to be compounding IV medications safely, was due to the simple fact that in 2006, in the state of Ohio, there were absolutely no requirements to become a pharmacy technician, aside from having your high school diploma. No training requirements, no continuing education requirements, no oversight by the Ohio State Pharmacy Board, no licensing or registration requirements, etc.

What is even more disturbing, is the fact that The Emily Jerry Foundation has been receiving an outpouring of concern from most people in the general public, as well as, the caregivers themselves, who were previously completely unaware that in all of our nation’s world renowned medical facilities, including the leading pediatric facility where Emily was treated, pharmacy technicians are the individuals responsible for compounding virtually all IV medications in the clinical pharmacy. It was this type of variability in quality, in terms of pharmacy technician requirements, coupled with the fact that the pharmacy technician’s overall scope of responsibilities have expanded greatly in recent decades, that led to the passage of Emily’s Law in the state of Ohio in January of 2009. Even though Emily’s Law significantly helped to reduce much of this variability in quality in the state of Ohio, this inherent problem is still very evident in many other states across the nation.

The Emily Jerry Foundation’s 2013 National Pharmacy Technician Regulation Scorecard highlights the states that are doing a great job of protecting their patients through strict controls and educational requirements for pharmacy techs, as well as encourage those that are lagging behind to make improvements in their own standards in order to improve care and potentially save lives. States like North Dakota received a perfect score based on the Foundation’s grading criteria. However, it’s now 2013 and six states still have no oversight by their respective state boards of pharmacy and, subsequently, no regulation regarding their pharmacy technicians. Numerous studies have shown that overall pharmacy error rates are volume dependent. (reference: USA Today, “Speed, high volumes can trigger mistakes”). With that fact in mind, pharmacy technician oversight and regulation issues like these, become even more of a serious matter of public safety in states like New York, which currently has the second highest prescription volume in the United States (253,796,344 Rx filled in 2012). (reference: SDI Health, L.L.C.: Special Data Request, 2012)

How should this variability in quality be fixed and subsequently managed?

Dr. Pronovost, together with his colleagues, in their paper, “Achieving the Potential of Health Care Performance Measures” propose seven recommendations:

1. Decisively move from measuring processes to outcomes;

2. Use quality measures strategically, adopting other quality improvement approaches where measures fall short;

3. Measure quality at the level of the organization, rather than the clinician;

4. Measure patient experience with care and patient-reported outcomes as ends in themselves;

5. Use measurement to promote the concept of the rapid-learning health care system;

6. Invest in the “basic science” of measurement development and applications, including an emphasis on anticipating and preventing unintended adverse consequences; and

7. Task a single entity with defining standards for measuring and reporting quality and cost data, similar to the role the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) serves for the reporting of corporate financial data, to improve the validity, comparability, and transparency of publicly-reported health care quality data.

Dr. Pronovost says the last proposal would bring about the most change:

Of the proposals, perhaps the biggest game-changer would be the creation of an entity to serve as the health care equivalent of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Rather than wading through a bevy of competing and often contradictory measures, patients and others would have one source of quality data that has national consensus behind it.

While the merits and demerits of a SEC for healthcare can be debated, one thing is clear from the comments posted in reply to Dr. Pronovost’s article – experts in specific areas should build consensus and determine what the ideal system should look like.

An example of the development of consensus is in checklists. The checklist developed by the Physician-Patient Alliance for Health & Safety reminds caregivers of the essential steps needed to be taken to initiate Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA) with a patient and to continue to assess that patient’s use of PCA.

Monitoring patients receiving opioids by patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is a critical patient safety issue. In its Sentinel Event Alert, “Safe Use of Opioids in Hospitals”, The Joint Commission recently stated:

While opioid use is generally safe for most patients, opioid analgesics may be associated with adverse effects, the most serious effect being respiratory depression, which is generally preceded by sedation.

More than 56,000 adverse events and 700 patient deaths were linked to PCA pumps in reports to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) between 2005 and 2009. One out of 378 post-surgical patients are harmed or die from errors related to the patient-controlled pumps that help relieve pain after surgical procedures, such as knee or abdominal surgery.

More recently, Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority released its analysis of medication errors and adverse drug reactions involving intravenous fentaNYL that were reported to them. Researchers found 2,319 events between June 2004 to March 2012 — that’s almost 25 events per month or about one every day. Although one error a day may seem high, their analysis is confined to reports made to the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority and only include fentaNYL, a potent, synthetic narcotic analgesic with a rapid onset and short duration of action.

Consequently, to provide greater patient safety, one of the recommended steps of the PCA Safety Checklist therefore provides:

Patient is electronically monitored with both:

pulse oximetry, and

capnography

The relentless push for quality and better patient safety must continue. To do otherwise will mean more Emily Jerrys and Amanda Abbiehls (who died after unmonitored use of a PCA).

For those of us who might think that death in a healthcare facility cannot happen to us or someone we know, Dr. Pronovost reminds us that preventable deaths is a leading cause of death. As he recently stated on The Katie Couric Show:

Frame the size of your problem. I suspect that all of your viewers either have been touched by or a family member has been harmed by mistakes. It is the third leading cause of death in this country. More people die from medical mistakes each year than died per year in the civil war.

So, make sure adequate training is provided for all those involved in healthcare delivery, like pharmacy technicians, and use checklists as a reminder of essential steps, such as the PCA Safety Checklist. It just may save a life.

Month: November 2013

The Emily Jerry Foundation and Codonics Partner at Upcoming American Society of Health System Pharmacists Midyear Meeting in Orlando Florida

Posted on November 2, 2013 by ejfadmin

When my two-year-old daughter, Emily, passed away from a tragic medication error in 2006, my primary concern as her father was to make sure that her story and the significant “lessons learned” be brought forward and that the internal systems in medicine be subsequently modified so that others wouldn’t suffer a similar fate, over and over again. Shortly after her death, I decided to become a full-time patient safety advocate, focusing the core of my work on being an active part of the solution to preventable medical errors. When I first began to educate myself on preventable medical errors in our nation, I was astonished to find that many sources were estimating that over 200,000 people die every year in the United States from preventable medical errors. In a more recent article from the Journal of Patient Safety (September 2013 – Volume 9 – Issue 3 – p 122–128) titled “A New, Evidence-based Estimate of Patient Harms Associated with Hospital Care”, I was completely horrified to find that now, in 2013, the revised estimated number of deaths from preventable medical errors in the United States is actually over 400,000 a year! This makes preventable medical errors in our nation the third leading cause of death, only after heart disease and cancer.

As Emily’s father, and more importantly, someone who has devoted the remainder of their life to being a patient safety and caregiver advocate focused on being a part of the solution, I’ve always taken issue with the simple word “preventable”. To me, the word “preventable” implies that we can, in fact, stop or impede something from happening only if we can acknowledge and anticipate that an event will occur and, consequently, implement the appropriate measures needed to “prevent” something from happening. However, with that notion in mind, in order to prevent something from happening (i.e., preventable medication errors, etc.), you absolutely must be PROACTIVE in terms of your approach to exactly what you’re trying to prevent. This is where The Emily Jerry Foundation’s key technology partner in patient safety, Codonics, and their Safe Label System (SLS) come into play at the upcoming American Society of Health System Pharmacists Midyear Meeting, in Orlando Florida, next week.

Category: News

The Need for Standards in Healthcare: For Improved Patient Safety and Quality of Care

Posted on November 1, 2013 by ejfadmin

by Christopher Jerry and Michael Wong

In his recent article, “A SEC for Health Care?”, Dr. Peter Pronovost, PhD, FCCM (Professor, Departments of Anesthesiology/Critical Care Medicine and Surgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Medical Director, Johns Hopkins Medicine Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality) discusses the tremendous variability in the quality and measures of healthcare provided across this country:

Depending where you look, you often get a different story about the quality of care at a given institution. For example, none of the 17 hospitals listed in U.S. News and World Report’s “Best Hospitals Honor Roll” were identified by the Joint Commission as top performers in its 2010 list of institutions that received a composite score of at least 95 percent on key process measures.

As an illustration of the variability of quality, the Emily Jerry Foundation recently released its “2013 National Pharmacy Technician Regulation Scorecard”. The development of this scorecard was prompted by the heartbreaking story of what happened to two year old Emily Jerry.

Emily had waged a successful battle against cancer. Her treatment had been so successful that her last MRI clearly showed that the tumor miraculously disappeared. In fact, three radiologists had to review her MRI films due to the fact that there wasn’t even any residual scar tissue left. Emily’s doctors said it was as if she never had cancer! Regardless she was scheduled to begin her last chemotherapy session on her second birthday, February 24, 2006. This last treatment was just to be sure that there were no traces of cancer left inside of her little body. Tragically, it was not cancer or the reoccurrence of cancer that ended Emily’s life. She was killed by an overdose of sodium chloride in the last chemotherapy IV bag she received.

Shortly after Emily’s tragic death, it was determined that a pharmacy technician, who did not have the proper training or core competency to be compounding IV chemotherapy, had made the deadly compounding error. The primary reason the pharmacy technician involved in Emily’s death lacked the core competency to be compounding IV medications safely, was due to the simple fact that in 2006, in the state of Ohio, there were absolutely no requirements to become a pharmacy technician, aside from having your high school diploma. No training requirements, no continuing education requirements, no oversight by the Ohio State Pharmacy Board, no licensing or registration requirements, etc.

What is even more disturbing, is the fact that The Emily Jerry Foundation has been receiving an outpouring of concern from most people in the general public, as well as, the caregivers themselves, who were previously completely unaware that in all of our nation’s world renowned medical facilities, including the leading pediatric facility where Emily was treated, pharmacy technicians are the individuals responsible for compounding virtually all IV medications in the clinical pharmacy. It was this type of variability in quality, in terms of pharmacy technician requirements, coupled with the fact that the pharmacy technician’s overall scope of responsibilities have expanded greatly in recent decades, that led to the passage of Emily’s Law in the state of Ohio in January of 2009. Even though Emily’s Law significantly helped to reduce much of this variability in quality in the state of Ohio, this inherent problem is still very evident in many other states across the nation.

The Emily Jerry Foundation’s 2013 National Pharmacy Technician Regulation Scorecard highlights the states that are doing a great job of protecting their patients through strict controls and educational requirements for pharmacy techs, as well as encourage those that are lagging behind to make improvements in their own standards in order to improve care and potentially save lives. States like North Dakota received a perfect score based on the Foundation’s grading criteria. However, it’s now 2013 and six states still have no oversight by their respective state boards of pharmacy and, subsequently, no regulation regarding their pharmacy technicians. Numerous studies have shown that overall pharmacy error rates are volume dependent. (reference: USA Today, “Speed, high volumes can trigger mistakes”). With that fact in mind, pharmacy technician oversight and regulation issues like these, become even more of a serious matter of public safety in states like New York, which currently has the second highest prescription volume in the United States (253,796,344 Rx filled in 2012). (reference: SDI Health, L.L.C.: Special Data Request, 2012)

How should this variability in quality be fixed and subsequently managed?

Dr. Pronovost, together with his colleagues, in their paper, “Achieving the Potential of Health Care Performance Measures” propose seven recommendations:

1. Decisively move from measuring processes to outcomes;

2. Use quality measures strategically, adopting other quality improvement approaches where measures fall short;

3. Measure quality at the level of the organization, rather than the clinician;

4. Measure patient experience with care and patient-reported outcomes as ends in themselves;

5. Use measurement to promote the concept of the rapid-learning health care system;

6. Invest in the “basic science” of measurement development and applications, including an emphasis on anticipating and preventing unintended adverse consequences; and

7. Task a single entity with defining standards for measuring and reporting quality and cost data, similar to the role the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) serves for the reporting of corporate financial data, to improve the validity, comparability, and transparency of publicly-reported health care quality data.

Dr. Pronovost says the last proposal would bring about the most change:

Of the proposals, perhaps the biggest game-changer would be the creation of an entity to serve as the health care equivalent of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Rather than wading through a bevy of competing and often contradictory measures, patients and others would have one source of quality data that has national consensus behind it.

While the merits and demerits of a SEC for healthcare can be debated, one thing is clear from the comments posted in reply to Dr. Pronovost’s article – experts in specific areas should build consensus and determine what the ideal system should look like.

An example of the development of consensus is in checklists. The checklist developed by the Physician-Patient Alliance for Health & Safety reminds caregivers of the essential steps needed to be taken to initiate Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA) with a patient and to continue to assess that patient’s use of PCA.

Monitoring patients receiving opioids by patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is a critical patient safety issue. In its Sentinel Event Alert, “Safe Use of Opioids in Hospitals”, The Joint Commission recently stated:

While opioid use is generally safe for most patients, opioid analgesics may be associated with adverse effects, the most serious effect being respiratory depression, which is generally preceded by sedation.

More than 56,000 adverse events and 700 patient deaths were linked to PCA pumps in reports to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) between 2005 and 2009. One out of 378 post-surgical patients are harmed or die from errors related to the patient-controlled pumps that help relieve pain after surgical procedures, such as knee or abdominal surgery.

More recently, Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority released its analysis of medication errors and adverse drug reactions involving intravenous fentaNYL that were reported to them. Researchers found 2,319 events between June 2004 to March 2012 — that’s almost 25 events per month or about one every day. Although one error a day may seem high, their analysis is confined to reports made to the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority and only include fentaNYL, a potent, synthetic narcotic analgesic with a rapid onset and short duration of action.

Consequently, to provide greater patient safety, one of the recommended steps of the PCA Safety Checklist therefore provides:

Patient is electronically monitored with both:

pulse oximetry, and

capnography

The relentless push for quality and better patient safety must continue. To do otherwise will mean more Emily Jerrys and Amanda Abbiehls (who died after unmonitored use of a PCA).

For those of us who might think that death in a healthcare facility cannot happen to us or someone we know, Dr. Pronovost reminds us that preventable deaths is a leading cause of death. As he recently stated on The Katie Couric Show:

Frame the size of your problem. I suspect that all of your viewers either have been touched by or a family member has been harmed by mistakes. It is the third leading cause of death in this country. More people die from medical mistakes each year than died per year in the civil war.

So, make sure adequate training is provided for all those involved in healthcare delivery, like pharmacy technicians, and use checklists as a reminder of essential steps, such as the PCA Safety Checklist. It just may save a life.

Category: News

Our Mission

The Emily Jerry Foundation is determined to help make our nation’s, world renowned, medical facilities safer for everyone, beginning with our babies and children. We are accomplishing this very important objective by focusing on increasing public awareness of key patient safety related issues and identifying technology and best practices that are proven to minimize the “human error” component of medicine. Through our ongoing efforts The Emily Jerry Foundation is working hard to save lives every day.

Recent Posts

Archives